Email and Text

Email messaging has been a fixture in most modern business organizations for the past few decades. Though other new and perhaps even more efficient means of communication are developed all the time, email continues to show its staying power. Indeed, most recent studies suggest that up to 95% of all business organizations still consider email to be their primary means of professional communication (Despite New Technologies, 95% of Companies Still Use Email). This means that in addition to having concrete skills and industry-specific knowledge, most employers are also expecting potential employees to be effective written communicators—specifically when it comes to email.

Whether you are currently employed or not, the skills that you will learn throughout this lesson will help you in many aspects of your life—whether it be in constructing an email to your child’s teacher, or deciding whether to text or email the leader of a ward auxiliary with a question or concern that you have.

In the Oral vs. Written Communication Writing Lesson, you learned what type of communication to use and when. Throughout this lesson, you will learn how to use that type of communication once you determine that it is the best one to use. More often than not, that method will likely be email.

There are some definitive best practices that you can use to ensure that your email communication remains professional and well-received. In this lesson, we will review a few of them so that you can start mastering this important skill.

Know your Audience

“Audience shapes message.” This principle holds true in nearly every situation of communication, email included. Before you draft or send any email communication, you must first consider who it is intended for. How close are you to this person? How familiar is this person to you and you to them? Is this message intended for a group or an individual? Is it being sent to a person or group of people that hold positions of authority or is it being sent to your best friend?

Your answer to these and other similar questions should inform the tone that you take in your email, as well as the subject line that you choose, your salutation, and even sign-off.

Ponder and Record

- How might an email to your best friend in the office differ from an email to your boss? How might the opening and closing lines of your email differ with each audience?

- How might an email sent to multiple employees of the office differ from an email being sent to just one person in the office? How might your opening and closing lines of the email differ with each audience?

Know your Purpose

Once you have considered and established your audience, the next important step that you can take is establishing the purpose of your email. In general, professional emails tend to fall into one of two categories: 1) request and reply emails or 2) confirmation emails.

Types of Emails

Most workplace emails tend to fall into the “request and reply” email category. Request emails typically require a reply or response of some kind. These kinds of emails ask questions, specify tasks others need to complete, ask for opinions or acknowledgments of policies or procedures, or provide assignments for meetings or projects.

Confirmation emails, on the other hand, serve the purpose of providing a permanent, written record of a conversation that has taken place. For example, perhaps you and your coworkers had a working lunch where you discussed an upcoming project. Details were sorted out and assignments were given, but there is no written record of that happening. In such a case, someone might be tasked with sending out a follow-up email, confirming what was discussed and what assignments were issued so that no one forgets or can claim ignorance later on.

These two types of emails are fundamentally different in their purpose in that, one is generally introducing new information and therefore should request a response from the recipient (request and reply emails) while the other is more informative and many times does not require a reply (confirmation emails).

Know the Format

Once you have established your audience as well as the purpose of your email, you are ready to begin writing it. In general, the most effective request and reply and confirmation emails tend to include at least the following:

- Appropriate salutation and subject line

- Background information

- Your ask

- Conclusion or next steps

Appropriate Salutation and Subject Line

As mentioned in the “audience” section, your relationship with the recipient and the intended purpose of the communication will indicate how formal or informal the salutation and subject line should be. Just as you would never address an email to a dear friend with “To whom it may concern,” it would be wise to not address an email to a close coworker with a similar formal tone. Likewise, you would never approach an unfamiliar, high-ranking government official with an informal, “Hey, how ya doin’?” You would also avoid communicating with your company’s CEO with a similarly informal tone.

Part of knowing your audience is knowing what a natural greeting to him or her might be. As Daniel Post Senning, an etiquette expert at the Emily Post Institute has advised, a good place to start is generally with an assessment of your unique professional community and its traditional conventions. He advises, “See what someone else is doing and participate, play along, sort of acknowledge the way communication develops and the way expectations in a relationship develop” (How to Write the Perfect Email). From there, you can then pattern your own behavior using the established communication conventions in your professional community as your guide.

The salutation of the email is only half the battle. Far too often, people tend to ignore one of the most important components of the email communication: the subject line.

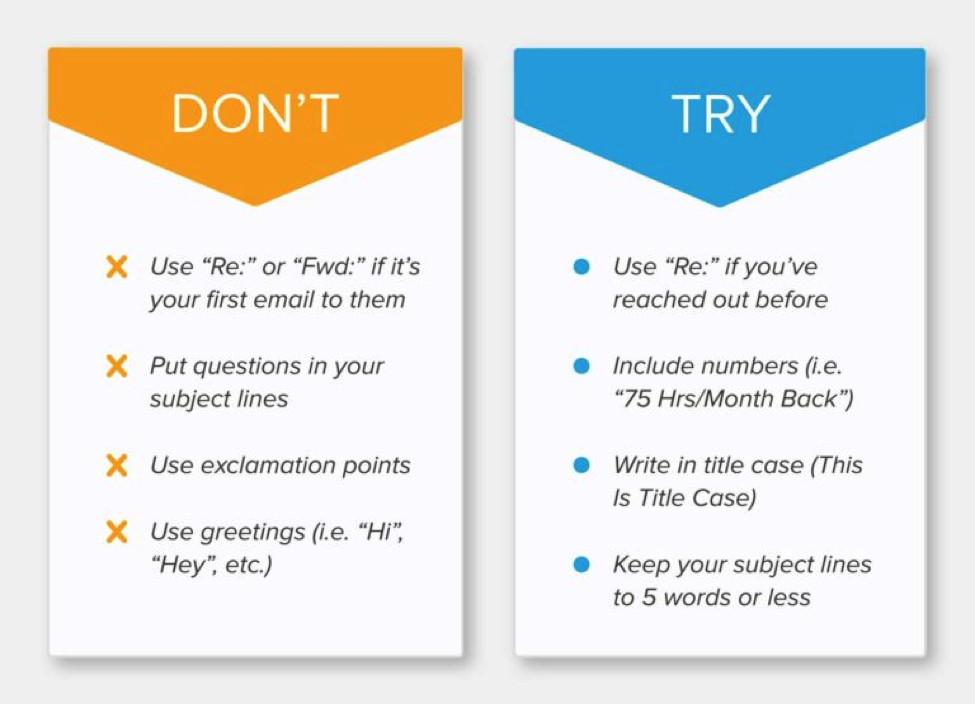

The subject line is what people first see when receiving email communication. Aside from the name of the sender, it is one of the primary determiners of whether or not that email gets opened. It also serves as a placeholder for all future email communication (particularly in the case of request and reply emails) as those have a tendency to become long threads of replies upon replies. As such, there are a few tips and tricks you should remember when deciding upon a subject line (How to Write a Professional Email Fast):

Background Information

Once the appropriate subject line and salutation have been created, your next step should be providing your reader with some background information. Questions to consider when drafting this section could be why are you sending this email? What is its purpose? How does the reader fit into this conversation?

Emails that start off by establishing the “ask” without the proper background tend to come off as cold, distant, and sometimes even demanding. Take the email below, for example:

Charles,

I understand that you are in charge of creating expense reports. I am in need of one by tomorrow at noon. Please send over your completed report ASAP.

—Jessica

Imagine for a second that this email is the first communication Jessica has ever sent to Charles. How might he be feeling if this is all the information that he is given? Might he feel taken advantage of, underappreciated, or even pushed around? Now, compare the email above to this one that provides Charles with a little bit of background information.

Charles,

My name is Jessica Rivera and I work in the Communications department. I just got out of a meeting with James Jones, and he mentioned that you are the one in charge of creating departmental expense reports.

I know it is short notice, but I am up against a deadline here, and I am wondering if you could put an expense report together for our department by tomorrow at noon. I know this might be pushing some of your own workload back by asking for this, so if there is anything that I can do to help, please let me know. I will do whatever it takes to make this happen.

Let me know if this is something that you feel you could do for me as soon as possible. I’ll await your reply.

Warm regards,

Jessica Rivera

Ponder and Record

- What background information does Jessica provide Charles with in the second email?

- What purpose does it serve?

- How might Charles’ response be different knowing what he now knows about Jessica’s predicament?

- Consider for a moment that this is not Jessica’s first email to Charles. Consider that maybe they are even good friends. How might the background information provided change? Would it still be necessary?

Your Ask

The next section of a polished, professional email generally serves the purpose of establishing the “ask” or purpose of the email. As shown in the email example above, Jessica’s “ask” is that Charles create an expense report for her:

I know it is short notice, but I am up against a deadline here. I was wondering if you could put an expense report together for our department by tomorrow at noon. I know this might be pushing some of your own workload back. If there is anything I can do to help, please let me know. I will do whatever it takes to make this happen.

When establishing “asks,” it is a good best practice to not only acknowledge your needs but also how those needs might impact your reader and his schedule and workload. It shows empathy and understanding while still establishing and maintaining the work that needs to be completed. Notice how Jessica does so in the email above when she states:

I know this might be pushing some of your own workload back. If there is anything I can do to help, please let me know. I will do whatever it takes to make this happen.

Ponder and Record

- What difference do you think Jessica’s acknowledgment of Charles’ workload might make (if any)?

- How could you ensure your “ask” is established early on in the email? What steps could you personally take to make that change in your own email correspondence?

Conclusion or Next Steps

The final portion of your email should be your conclusion and/or “next steps” section. Given the nature of the “request and reply” emails, it is generally expected that recipients will be required to respond in some way (whether to confirm they received the email, understand their task, or even just ask clarifying questions). None of these things are likely to happen without a proper conclusion that includes an invitation to act or respond.

How might Jessica’s email be different without the addition of this conclusion?

Let me know if this is something you feel you could do for me as soon as possible. I’ll await your reply.

Do you think Charles would respond to her email? Without an invitation to reply back and confirm his availability, how would Jessica know if Charles is up for fulfilling the assignment by the appointed deadline?

It is always a good idea to not only express gratitude but also indicate what action needs to be taken—what outcome is expected to occur because of this email being sent and received.

Be Professional

One final thing that you should always keep in mind when creating a quality email in the workplace is professionalism. As you learned in previous writing lessons, one of the easiest ways to be rejected from your desired professional community is to fail to communicate at the level that others within that professional community communicate. In many professional situations, this means that using things like emojis, ALL CAPS, text-speak (like PLZ, LOL, BTW, IDK, etc.), excessive punctuation (like multiple exclamation marks), or even incorrect punctuation could result in your rejection from the professional community that you are trying to write into. It is imperative that you always strive to maintain a professional tone and manner of speaking (even when communicating with coworkers who are close friends). Always make an effort to proofread your email before you send it.

Another mark of professionalism in writing is being clear and concise. As you learned in the Oral vs. Written Communication lesson, it is important to take into account the recipient’s familiarity with the topic and need (or lack thereof) for context.

Most professional communities discourage sending emails that are longer than a few, short paragraphs (in other words, emails that contain more than just a brief background, an ask, and a conclusion or next steps request). If you find that your email is growing longer due to a need for a lot of background, a complicated or unfamiliar “ask,” or even a large and diverse audience, consider changing your tactic. Would email be the best forum to relay this information? Would it be better in a one-on-one or group meeting? Could it be better accomplished with a phone call or video conference, followed by a confirmation email?

Whatever communication challenge you encounter, strive to remember what you have learned in this and other writing lessons and choose the proper method and means for communicating that message based on the professional community’s goals, values, and preferred methods of communication.

So, just to recap, some best practices to keep in mind when creating a professional email are the following:

- Know your audience

- Know your purpose

- Know the format

- Be professional